The Kingdom of Benin was a vast, advanced, and powerful civilization located in present-day Nigeria. With a rich history spanning over 1,600 years, Benin was one of West Africa’s longest-lasting states, ruled by the Oba Dynasty for 600 years and the Ogiso Dynasty for 1,000 years. This kingdom boasts an impressive legacy, featuring a sophisticated infrastructure that includes a majestic capital city, an extensive network of earthworks surpassing the Great Wall of China in scale, and renowned artwork that showcases the kingdom’s rich cultural heritage.

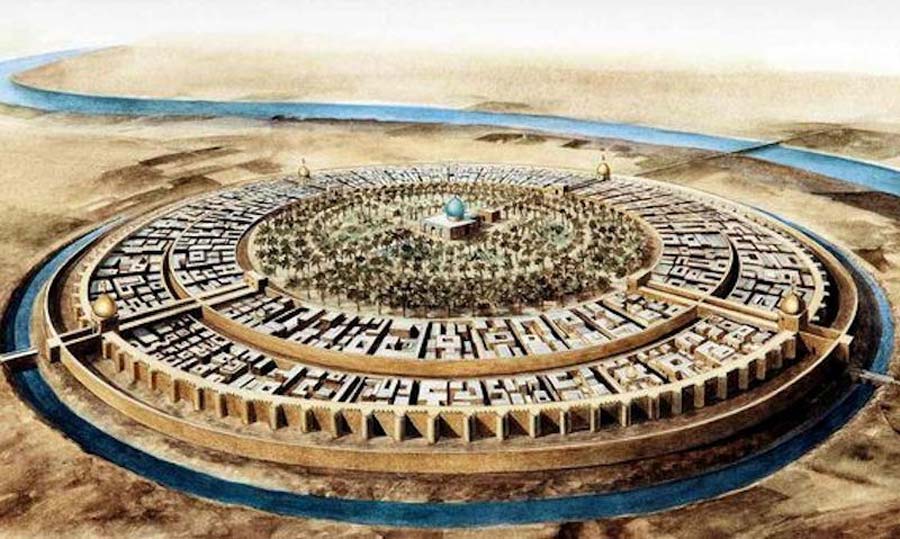

At its peak in the 14th century, the Benin Kingdom’s capital city was a marvel of advanced urban planning, surpassing European cities like Lisbon and London. Its impressive architecture, street lighting, and organized road network set it apart. Today, the Edo people and neighbouring states in southern Nigeria claim direct descent from this ancient kingdom. It should be noted that the Kingdom of Benin has no historical connection to the current day republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. To understand the British invasion of Benin, it’s essential to examine the empire’s rich history, including its origins and the various dynasties that ruled this ancient power.

The Origin of Kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin originated as a confederation of towns and villages, evolving into the kingdom of Igodomigodo under the Ogisos, or “Sky Kings.” This era, marked by a blend of mythology and reality, lasted until the 12th century when the Oba Dynasty was founded, ushering in a more historical period. Both Benin and Edo rose to prominence, laying the groundwork for the empire’s future growth. The Ogiso and Oba dynasties coexisted briefly before splitting, ending the Igodomigodo Kingdom and beginning the Benin Empire.

According to legend, the Ogiso Dynasty ended with the exile of King Ogiso Owodo, who was banished for killing a pregnant woman. This event marked the end of Ogiso rule in Igodomigodo, paving the way for the Benin Empire’s rise. Ogiso Owodo’s incompetence and offence led to widespread suffering and instability, compromising royal authority. After his expulsion, a prominent elder was elected as head of state and initially ruled without issues. However, when he attempted to appoint his son as successor, the other elders opposed the decision. Instead, they sought leadership from Oduduwa, a Yoruba king from Ile-Ife. Some accounts suggest Oduduwa was the exiled son of Ogiso Owodo, but Yoruba accounts dispute this, arguing that Oduduwa was sought due to his reputation as a powerful and respected ally who had previously protected Igodomigodo from foreign invasions.

The elders of Igodomigodo chose Oduduwa to rule, seeking to avoid internal rivalries. However, Oduduwa declined and instead sent his youngest son, Oranmiyan, to take the throne. Oranmiyan accepted and moved to Usama, where he married a local noble’s daughter and had a son, Eweka. Despite this, Oranmiyan’s unconventional governance style faced strong resistance from local nobles, leading him to abandon his position. Before leaving, he named the land “Ile-Ibinu” or “The Land of Vexation,” later shortened to “Ubinu,” a denomination that would continue. Eweka, Oranmiyan’s son, was raised in Benin by his mother, giving him a rightful claim to the throne. Although his mixed heritage with a Yoruba father from Ile-Ife set him apart, Eweka’s distinct identity became a hallmark of his remarkable leadership throughout Benin’s history.

The decision of Oranmiyan to renounce his title and install Eweka as king stemmed from his belief that a locally born and raised individual was best suited to govern the land. This move allowed Eweka to become the first Oba of Benin and laid the foundation for the Dynastic Myth, legitimizing the monarch’s authority. After returning to Yoruba land, Oranmiyan went on to found the powerful Oyo Empire, which extended his legacy beyond Benin and shaped Yoruba history. The ascension of Eweka marked the beginning of the Oba era, Benin’s second monarchical system, which had a lasting impact on the kingdom’s governance and traditions.

The Era of the Oba’s, Benin’s Golden Age and Prosperity

The Oba era saw a revival of traditions and symbolism from the Ogiso period, with the Obas emerging as semi-divine rulers. Unlike the Ogisos, the Obas didn’t hold absolute power; instead, they worked with local hereditary nobles who handled key matters and collected tribute. This symbiotic relationship maintained balance and stability, with the Oba’s approval granting legitimacy to the nobles’ administrative powers. The Uzama, a council of nobles, served as kingmakers and regulated the Oba’s power, selecting a successor from among his sons after his death. However, this significant authority sometimes led to tensions between the Uzama and Obas.

A turning point came with the ascension of Oba Ewuare in the 15th century. Born Prince Ogun, Ewuare’s early life was marked by turmoil. His father, Oba Ohen, was deposed and executed by the Uzama, and subsequent Obas faced similar challenges. Ewuare’s own path to the throne was fraught with difficulty, including capture by the Uzama and a daring escape with the help of a slave named Edo. In gratitude, Ewuare later named his city after Edo, which became the namesake of the Edo Empire and people.

Upon securing the throne in 1440, Ewuare took steps to prevent future power struggles. He abolished the Uzama’s authority to select the Oba, introducing a system of primogeniture where the eldest son would inherit the throne. Ewuare also established the title of Edaiken for his eldest sons and appointed each son to govern a town, providing them with valuable leadership experience. Additionally, he created two new administrative orders, Eghabho n’ore and Eghabho n’ogbe, comprised of officials handpicked by the Oba and directly accountable to him. This consolidation of power paved the way for Ewuare’s notable achievements, earning him the title of “Ewuare the Great.

Under Ewuare’s leadership, Benin transformed into a vast empire, expanding from a city-state to incorporate surrounding regions, including both Edo and non-Edo groups, and reaching the coast. The empire’s growth accelerated during the reign of Ozolua the Conqueror (1480-1504), Ewuare’s son, roughly doubling its size. Benin reached its zenith under Oba Orhogbua, who conquered the area now known as Lagos. Despite its predominantly Edo core, the empire didn’t impose Edo culture on its territories, instead embracing rich cultural and linguistic diversity. This diversity led to the evolution of the capital’s name from Ubinu to “Bini” and eventually Benin.

The kingdom’s strategic location along the coast and near the Niger River generated immense wealth through lucrative fees collected from controlling the waterways. The empire’s prosperity was matched by its military prowess, expanding territories and yielding vast tributes from neighboring kingdoms. As the kingdom’s influence and wealth grew, it attracted skilled artisans, including cloth makers, bronze sculptors, and carpenters, seeking new opportunities and prosperity.

Ewuare fostered a thriving artistic culture in Benin by directly commissioning and purchasing art for his personal collection. This patronage led to the creation of exquisite sculptures in brass, ivory, and iron, which showcased the kingdom’s rules, traditions, and rituals. Ewuare also oversaw the construction of the inner wall of Benin City, part of the Walls of Benin network. The defensive structure consisted of deep moats and artificial hills made from excavated soil, with vegetation-filled barriers that hindered crossing.

The construction of the inner walls was a massive undertaking, requiring an estimated 5,000 labourers working 10 hours a day. The kingdom’s engineering prowess was demonstrated by the impressive earthworks, which featured ditches up to 15 meters deep and over 15 meters wide.

The construction of the Walls of Benin, or Iya, was a monumental task. The inner walls stood up to 50 feet tall, while the outer walls, though shorter at 25 feet, stretched an impressive 6,000 miles, making the Great Walls of Benin one of the longest human-made structures in history. The scale of the walls is breathtaking, with material usage estimated to be ten times that of the Great Pyramid of Khufu. While traditionally attributed to Oba Ogoula in the 13th century, evidence suggests a more complex origin story, with possible earlier beginnings or purposes beyond defense.

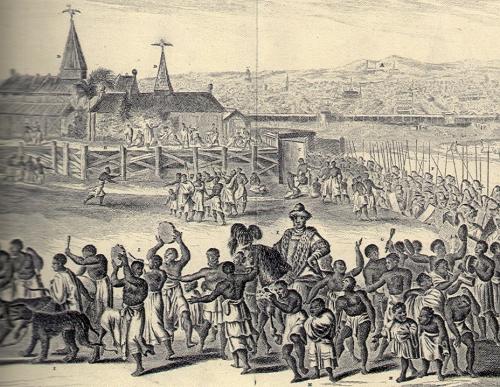

Benin City was also a pioneer in urban planning, being one of the earliest cities to feature streetlights. Towering metal lamps fueled by burning wicks illuminated the streets, facilitating nighttime traffic to and from the palace. The kingdom’s impressive infrastructure, including its extensive walls and well-planned thoroughfares, left a lasting impression on visitors from across Africa.

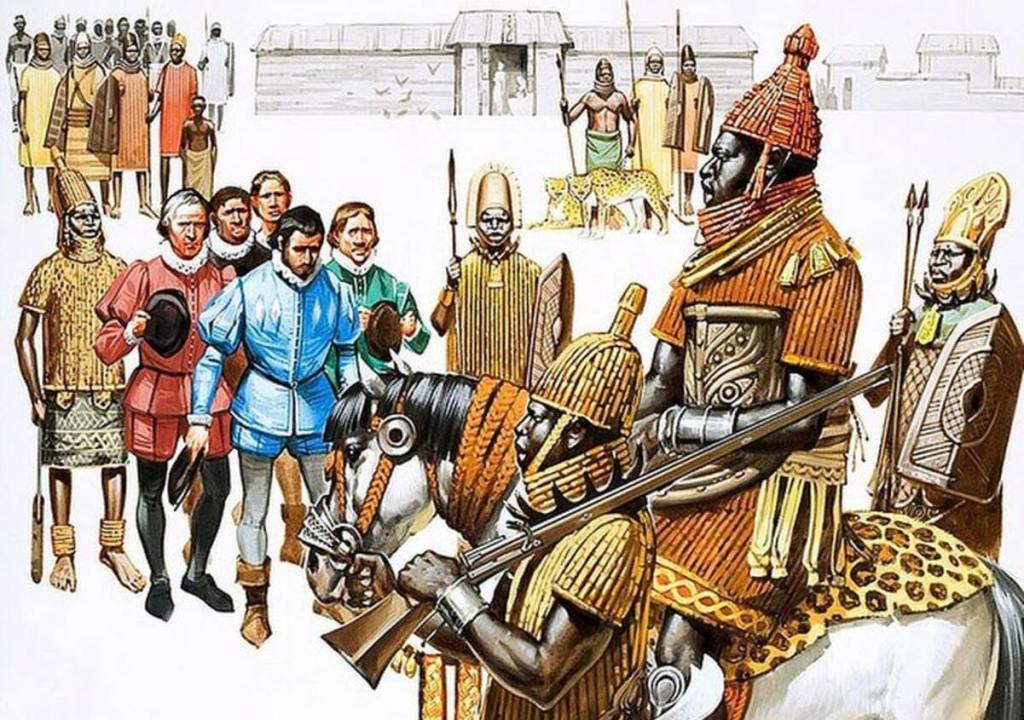

The Benin Kingdom flourished in the late 15th century, attracting visitors and traders worldwide, including Europeans. The Portuguese established the first European trade relations, followed by the English and Dutch in the 16th and 17th centuries. Benin served as Europe’s introduction to West Africa, with the Portuguese naming the surrounding bay in honor of the kingdom.

In 1485, the Portuguese arrived in Benin City and were astonished to find a vast, well-organized kingdom with numerous cities and villages in the African interior. They dubbed it the “Great City of Benin,” recognizing it as one of the few African cities worthy of the title. European visitors consistently ranked Benin City among the world’s most beautiful and well-planned urban centres. Lourenco Pinto’s observation about the Benin civilization in 1691 highlighted the city’s grandeur, noting that:

“Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown, and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

Olfert Dapper, a 17th-century Dutch visitor, also offered further insights into the city’s organization and architecture, stating that:

“Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other adorned with gables and steps. They are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

The source adds that these walls were kept “as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper storeys are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water”.

Olfert Dapper

Olfert Dapper continues by saying that:

“The king’s court is square and located on the right-hand side of the city, as one enters it through the gate of Gotton. It is about the same size as the city of Haarlem and surrounded by a special wall, comparable to the one which encircles the town. It is divided into many magnificent palaces, houses, and flats of the courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long squares with galleries, about as large as the Exchange in Amsterdam.

The buildings are of different sizes, however, resting on wooden pillars, from top to bottom lined with copper casts, on which pictures of their war exploits and battles are engraved. All of them are being very well maintained. Most of the buildings within this court are covered with palm leaves, instead of with square planks, and every roof is adorned with a small spired tower, on which cast copper birds are standing, being very artfully sculpted and lifelike with their wings spread.”

Olfert Dapper

The Benin Kingdom’s trade with Europeans involved exchanging local goods like ivory, palm oil, and manillas for valuable items and infrastructure. This trade helped expand their territory and solidify their regional power. The exchange brought the kingdom economic benefits and contributed to its growth and influence.

How Everything Went wrong for the Benin Kingdom

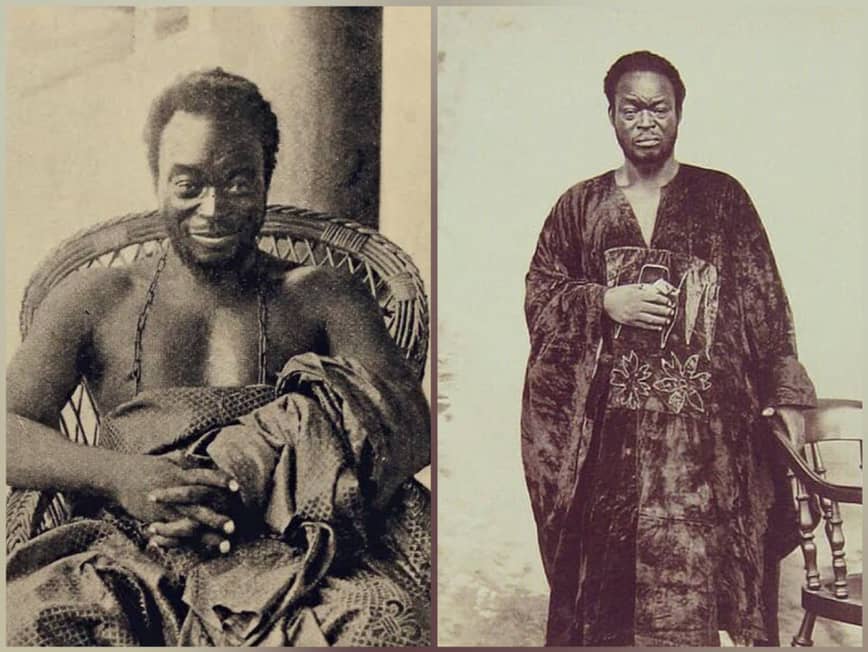

The Benin Kingdom’s relations with Europeans deteriorated as the British Empire sought to exploit the kingdom’s wealth and assert dominance over African territories. Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi grew concerned as neighbouring kingdoms fell to British control, and the fate of leaders like King Jaja of Opobo and Chief Nana of Itsekiri served as a warning.

Oba Ovonramwen restricted trade opportunities, including palm kernel trade, in response to British dominance over neighbouring kingdoms. The British saw this as a threat and began plotting to invade Benin, seeking a pretext to justify their actions. They used a familiar tactic, such as forcing the Oba to sign a one-sided agreement.

Lieutenant Henry Gallway was tasked with securing the Gallwey Treaty in 1892, with the goal of annexing Benin as a British colony and gaining control over its trade and territory.

Lieutenant Gallway presented the treaty to Oba Ovonramwen, but a language barrier likely hindered the Oba’s understanding. Suspecting British ulterior motives, the Oba refused to sign, instead instructing his advisors to review the document to stall for time and appease the British. However, some of his subjects may have secretly signed without his knowledge or consent. The British considered this a binding agreement, granting them unrestricted trade access, while the Oba viewed it as meaningless.

Oba Ovonramwen continued Benin’s centuries-old customs, including collecting tributes from traders, unaware that the British considered this a treaty violation. The British issued an ultimatum to the Oba, warning him that he must cease the practice or face armed conflict. The Oba ignored the warnings and continued to rule as usual. This triggered a confrontation between the Benin Kingdom and the British Empire.

The Conflict that ended the Benin Empire

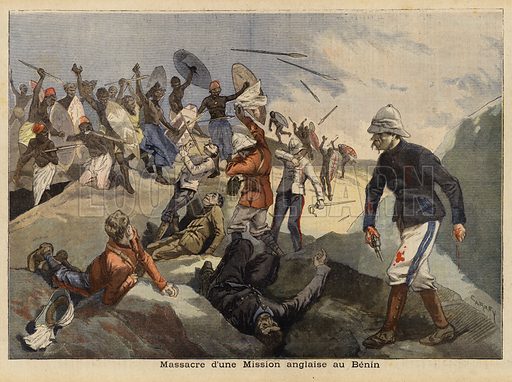

In 1896, James Robert Phillips, Acting Consul-General of the Niger Coast Protectorate, planned to meet with the Oba of Benin to discuss trade agreements. However, his visit coincided with the Igue Festival, a significant event in the Benin Kingdom. The Oba requested that Phillips postpone the meeting until after the festival, as it was a time when the Oba was ritually forbidden from interacting with foreigners.

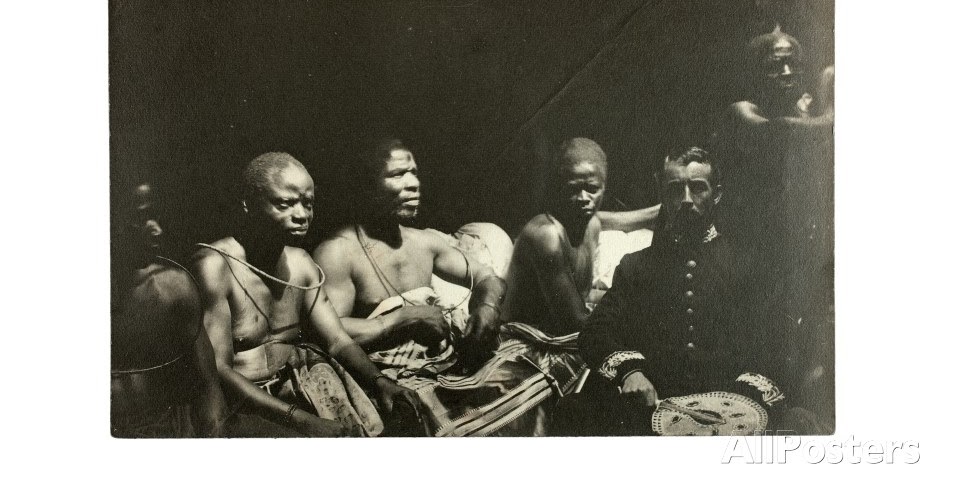

Ignoring Oba Ovonramwen’s warning, James Phillips led a British expedition to Benin, resulting in an ambush on January 4, 1897. The ambush killed six British officials and over 200 African porters. The British responded with a punitive expedition led by Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson, commanding 1,200 men. The British captured Benin City on February 18, 1897, after a series of battles.

The Benin forces were outnumbered and outgunned, leading to a brutal and one-sided battle due to British superior weaponry. Many Benin residents were killed, and their homes were destroyed. The kingdom was annexed, and Oba Ovonramwen was exiled to Calabar, marking the beginning of British colonial rule in Benin. The British looted the palace, confiscating thousands of art pieces, including the famous Benin Bronzes. Some artifacts were sold to pay for the expedition, while others were given to the British Museum. The once-thriving kingdom was abandoned, with far-reaching consequences for its people.

The British reported a relatively low number of casualties on their side. However, the impact on the Benin forces and citizens was substantial, with estimates suggesting many lives lost. The city suffered damage, and many of its treasures were removed by the British. Following the conflict, Ralph Moor, High Commissioner of the British Southern Nigeria Protectorate, reported on the sale of Benin ivory, indicating that some of the kingdom’s artistic treasures were sold to other European nations.

Oba Ovonramwen fled Benin City as the British pursued him. A reward was offered for information leading to his capture. The British warned that villages harbouring him would face consequences. Despite this, his loyal subjects helped him evade capture for several months.

On August 5, 1897, Oba Ovonramwen surrendered and was exiled to Calabar. He died in 1914. Six of his chiefs and subjects who aided his escape were executed by the British. The pursuit and its aftermath reflect the complexities of the period.

In 1914, Aiguobasinwin Ovonramwen, the son of Oba Ovonramwen, became the first Oba (Eweka II) under British colonial rule. Benin had ceased to be an independent nation, as it had come to be firmly under the jurisdiction and authority of the British. The once famous Benin Kingdom later became a protectorate in southern Nigeria. Nigeria achieved its independence in 1960, and the Benin kingdom, which is now known as Benin city in Edo state, has remained a part of Nigeria until the present day.

Thousands of bronze artifacts from the ancient Benin Kingdom are now scattered across European museums, with little hope of being returned to their rightful owners in Edo State, Nigeria. Valued at tens of billions of dollars, these relics are a prized possession for European institutions, which has motivated their decision to retain them despite being cultural treasures that belong to Nigeria.

Conclusion

This desire for power and wealth was reflected in the British colonization of Africa, which included the invasion of the Benin Kingdom. African kingdoms and empires were destroyed, cultures were erased, and resources were plundered. The indigenous populations were subjected to forced labour, land expropriation, and violent suppression. Today, the impact of these dark moments in history continues to be felt today.

Source

Soma’s Academy. (2022, September 30). The Kingdom of Benin (Edo Empire) | West Africa’s Longest Lasting State [Video]. YouTube.

Koutonin, Mawuna. “Story of Cities #5: Benin City, The Mighty Medieval Capital Now Lost without Trace.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, March 18, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/20

“Oba Orhogbua.” Edo World. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.edoworld.net/Oba_Orhogbua.html

Obinyan, Thomas Uwadiale. “The Annexation of Benin.” Journal of Black Studies 19, no. 1 (1988): 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934788019

“Ogiso Owodo.” Edo World. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.edoworld.net/Ogiso_Owodo…..

The empire of Benin and its cultural heritage | Revealing Histories. (n.d.). http://revealinghistories.org.uk/colonialism-and-the-expansion-of-empires/articles/the-empire-of-benin-and-its-cultural-heritage.html

Leave a reply to Cate Covert Cancel reply