Bosnia and Herzegovina is a European country located on the western Balkan Peninsula, with a short coastline on the Adriatic Sea. The country comprises two main regions: Bosnia, which covers the north and central areas, and Herzegovina, which spans the south and southwest. Its capital, Sarajevo, is a key regional hub, alongside other major cities like Mostar and Banja Luka.

The historical regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina do not align with the country’s modern-day political divisions. Established by the 1995 Dayton Accords, Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two entities: Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Read More: Is Croatia Safe for Black Travellers? A Nigerian’s Experience

Interestingly, the country has a unique geography, with its southernmost part, the Neum corridor, separating the two main areas and bordering Croatia. This unusual configuration raises a natural question: Why does Bosnia and Herzegovina have a territorial corridor that separates its two main parts, effectively creating a geographic anomaly?

How Everything started from a Historical Point of View

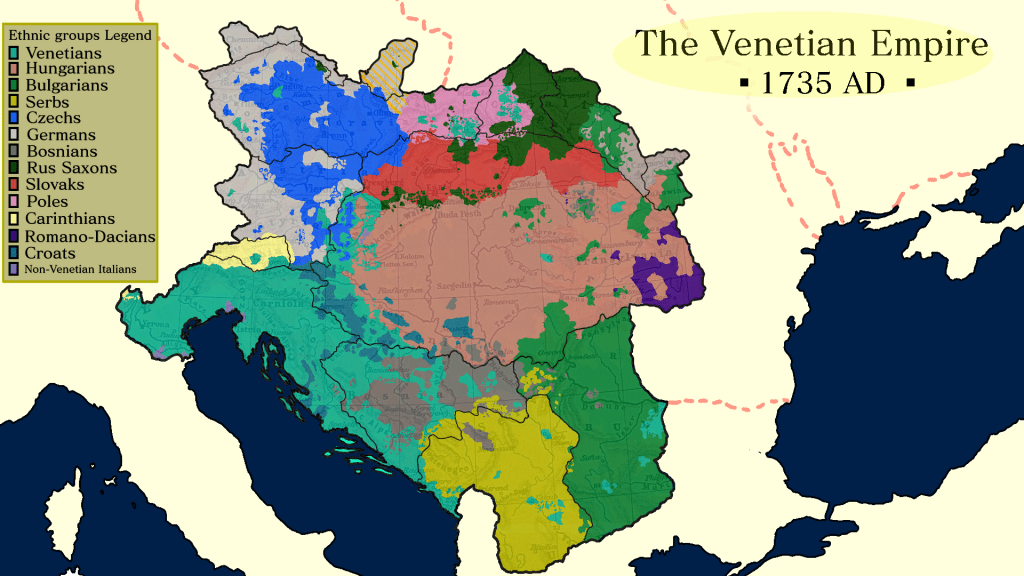

During the early modern period, Croatia was ruled by Hungarian dynasties, which frequently clashed with the Ottoman Empire to the south. However, not all of Croatia was under Hungarian influence. The Republic of Venice controlled Dalmatia, the southern region of Croatia, during the Renaissance.

Venice’s rule had a profound impact on Croatian culture, particularly in cities like Split, Zadar, and Dubrovnik. The Venetian-Ottoman rivalry resulted in frequent conflicts, eventually leading to a broader conflict between the empires.

The Ottoman-Venetian Wars (1396-1718) were a succession of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice. The Ottomans’ aspirations for expansion and Venice’s resolve to protect its crucial trade routes in the Mediterranean served as the main drivers of the wars.

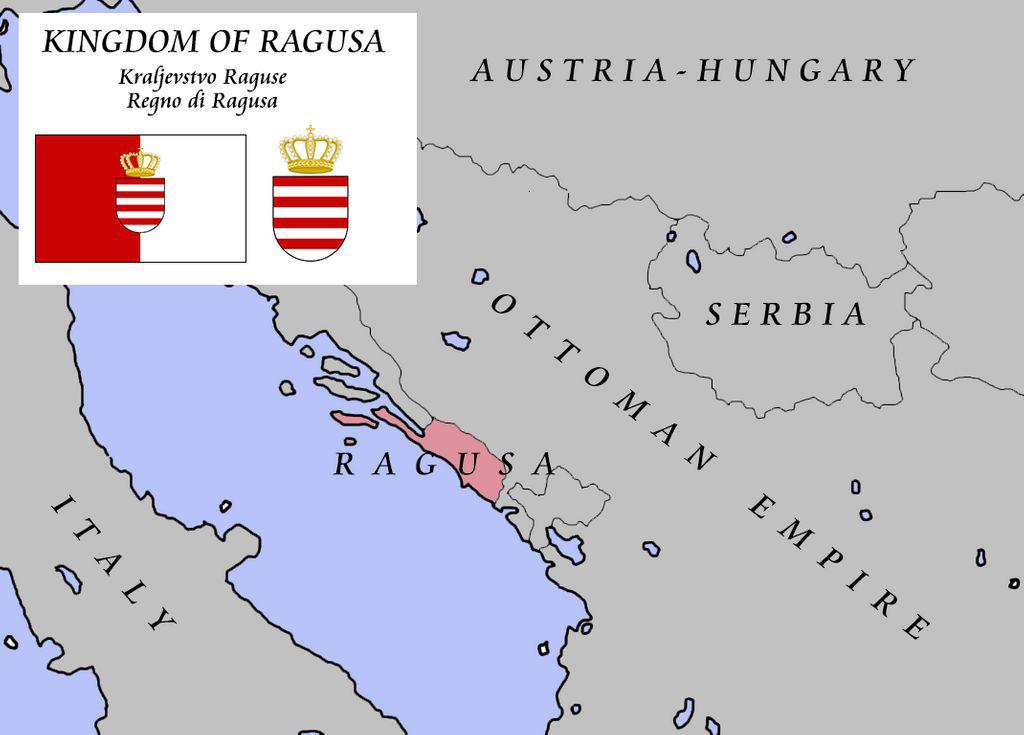

The Republic of Ragusa, also known as Dubrovačka Republika, gained independence from Venice in 1358. Previously, its Rector was appointed by Venice. The republic’s original name, Communitas Ragusina, was later changed to Respublica Ragusina in the 14th century. Today, the city is known as Dubrovnik.

It is important to note that the Ragusa Republic was a sovereign merchant state that skilfully maintained its independence between the Ottoman and Venetian Empires. Considered one of the most advanced nations of its time, Ragusa was part of the Hungarian-ruled Croatian lands but operated largely autonomously from the Buda court.

Ragusa formed a strategic alliance with the Ottoman Empire to protect itself from Venetian invasions. In exchange, Ragusa acknowledged Ottoman supremacy, paid an annual tribute, and gave the Ottomans control of parts of its coast, including Neum and Sutorina. The alliance increased Ragusan merchants’ trading power by allowing them to trade across the Ottoman Empire and access the Black Sea.

The Ottoman-Ragusa Treaty guaranteed Ragusa’s protection against Venetian invasions, discouraging Venice from attacking for fear of Ottoman retaliation. Ragusa benefited from this alliance for nearly 150 years until Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory over Austria led to its annexation by the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in 1808, marking the end of its independence.

The Republic of Ragusa was eventually defeated by French forces in 1806, following a Russian siege that bombarded the city with 3,000 cannonballs. Marshal Marmont, appointed “Duke of Ragusa” in 1801, abolished the republic and merged it with the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy.

Following Napoleon’s defeat, Ragusa was absorbed into the Habsburg Empire (1814-1918), which also ruled Austria from 1282 to 1918. Ragusa was a valuable economic region for the Habsburgs, despite aspirations for independence, and was merged into the Austrian and then Austro-Hungarian Empires.

The annexation of Ragusa impacted neighbouring Bosnia, which was occupied by the Habsburg Austria-Hungarian Empire in 1878. Bosnia’s complex status under Ottoman rule and Austrian occupation made change impractical. Ragusa’s economic integration with the empire over three decades made independence unlikely. The Bosnian administration maintained the status quo.

Austria-Hungary’s entry into World War I led to its downfall, and the Habsburg Empire dissolved. Its territories were divided, with some falling under the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Ragusa, now known as Dubrovnik, became part of Yugoslavia in 1929, officially adopting its new name after the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s collapse. Territorial disputes with Bosnia were settled after the creation of Yugoslavia.

The northern part of Bosnia became part of the Banovina, while the southern part joined the Zidovina Banovina. However, this ethnic-based reorganization would later become a contentious issue. The resolution of the territorial anomalies has led some to question the legitimacy of Bosnia’s ownership of the corridor, with Josip Broz Tito being the key figure behind this decision.

During World War II, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria) on April 6, 1941. The country was divided into two states: one aligned with the Nazis and the other with the communists. However, by the end of the war, Josip Broz Tito’s communist-led partisan forces had liberated and reunified the country.

Josip Broz Tito’s communist government took power in Yugoslavia after its liberation. Tito’s partisan forces, though mostly communist, included diverse political affiliations. Tito’s success stemmed from his guerrilla tactics, charisma, and vision for a federated Yugoslavia. His army’s victories outpaced those of rival leader Mihajlović and the chetniks.

Josip Broz Tito’s power grew rapidly. By 1943, he commanded a large army and controlled much of Yugoslavia, centered in Bosnia. He received Soviet support initially, then full backing from the British and Americans by 1944. Tito negotiated a merger between the royal government and his council in 1944. He became Yugoslavia’s first president in 1945, aiming to establish a neutral and independent state. To achieve this, Tito reorganized Yugoslavia’s internal divisions.

The government decided to maintain the Bosnia and Herzegovina-Croatia border, viewing ethnic divisions as artificial. As a result, the southern corridor was assigned to Montenegro instead of being returned to Bosnia. This arrangement remained until Yugoslavia’s dissolution. The international community then declared that any border changes would be invalid, ensuring that the original borders remained. This is why Croatia’s coastline still bears a significant Bosnian influence today.

The Pelješac bridge marks the end of a historic landmark split between Croatia and Bosnia

The Croatian government constructed the Pelješac bridge, bypassing a narrow Bosnian coastline strip, to connect its southern Adriatic region. Co-funded by the EU, the bridge spans from Komarna to Brijesta on the Pelješac peninsula and was inaugurated on July 26, 2022. This new infrastructure simplifies access to the popular tourist destination Dubrovnik.

In 2017, the EU contributed €357 million to the completion of the 55-meter-high Pelješac bridge. This 2.4-kilometer cable-stayed bridge shortens travel time along the Adriatic coast by 37 minutes. The inauguration is a significant milestone for Croatia and its neighbours, removing the need for residents and tourists to pass through Bosnia and Herzegovina and its lengthy border checks.

The Pelješac bridge was a significant milestone that ended the historical division that caused traffic disruptions and isolation in the Adriatic region. The bridge is expected to increase economic growth in South Dalmatia and Croatia, contributing to national unity and development.

Photo by Kenneth Sonntag on Unsplash

Fact Credit by CNN: New Croatia bridge redraws map of Adriatic coast

Leave a comment