It is unusual to see a country wage war on its own citizens. Normally, a country would be proud of the progress its citizens had made, but in America, this was not the case. Instead of celebrating the achievements of its African American citizens, they ganged up to destroy it.

May 31, 1921, will be remembered as the day White America turned on its African American citizens in Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma, a community that had thrived in the face of centuries of brutal oppression, slavery, and systemic inequality, only to be met with violence and destruction.

How Tulsa Became Known as Black Wall Street and a Haven of Black American Prosperity

Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a city on the rise in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, driven by the Land Run of 1889 and the discovery of oil. African Americans from the rural South, particularly those from Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, flocked to the city, drawn by the promise of economic opportunity and a new beginning.

The Greenwood District, strategically located in Tulsa, grew into a thriving center of African American entrepreneurship. Because of its remarkable concentration of wealth, businesses, and economic influence, this vibrant neighbourhood would eventually earn the moniker Black Wall Street.

Read more: How the One-Drop Rule Caused Confusion and Discrimination For Black People in America

As the oil industry expanded, many African Americans in Greenwood profited from oil-rich properties and royalties in the Glenn Pool, Red Fork, and Cushing oil fields, generating a consistent income and investing in their community. This influx of wealth and talent sparked a healthy entrepreneurial spirit, enabling Black Wall Street to flourish.

Hundreds of businesses, including banks, hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, barbershops, insurance agencies, real estate offices, and healthcare facilities, served the community.

Entrepreneurs capitalized on this momentum to create a diverse and resilient economy, transforming the Greenwood District into a thriving center for African American trade and culture.

This vibrant environment produced notable community leaders like O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford, who exemplified the entrepreneurial spirit. Gurley was a successful entrepreneur who owned several businesses, including a real estate company, a hotel, and the Gurley Hotel.

Stradford, a lawyer and businessman, owned many properties on Black Wall Street, including the Stradford Building and Stradford Hotel.

These individuals, along with many others, helped make Black Wall Street a vibrant hub of African American commerce and culture.

Unfortunately, as history has shown, the dream of a healthy black community came to an end when white America decided they would rather die than see the black man stand on his own two feet.

The Events that led to the Tulsa Massacre

A confrontation between a young black man named Dick Rowland and a white lift operator named Sarah Page on May 31, 1921, triggered a wave of racial violence that would destroy the community, bringing tensions to a head.

Note: There are no verified images of Sarah Page

The incident began when Rowland accidentally stepped on Page’s foot in the Drexel Building, where she worked. Fearing for his safety, Rowland fled the scene, but was later apprehended and detained after a white clerk reported the incident to authorities.

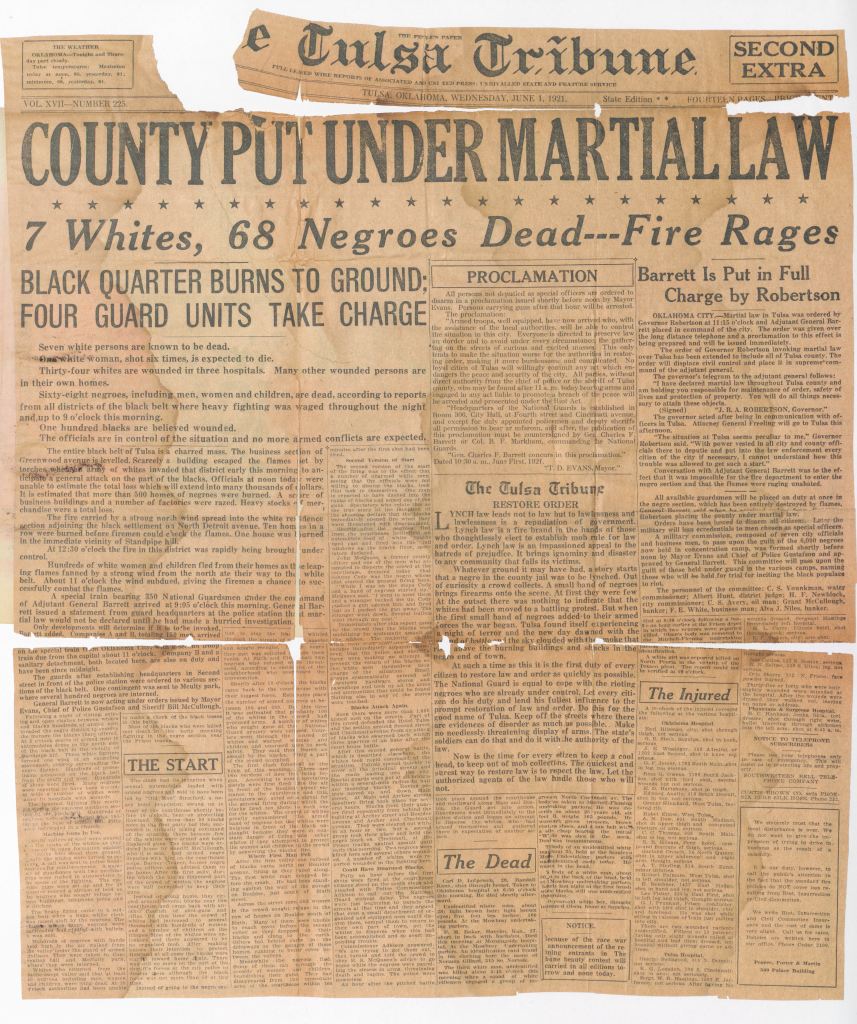

The situation seemed headed for a peaceful resolution, but everything changed when the Tulsa Tribune published an article titled “To Lynch a Negro” on May 31, 1921, claiming Rowland was to be lynched for allegedly assaulting a white woman.

The article, which appeared in the evening edition around 3-4 p.m, tripped outrage among white residents, who gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse demanding Rowland’s release, most likely created by existing tensions.

A group of black World War I veterans, led by respected leaders O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford, arrived at the courthouse armed and determined to defend their community. They formed a human barrier between the mob and Rowland, refusing to back down. This confrontation between the two groups was what triggered the Tulsa Race Massacre.

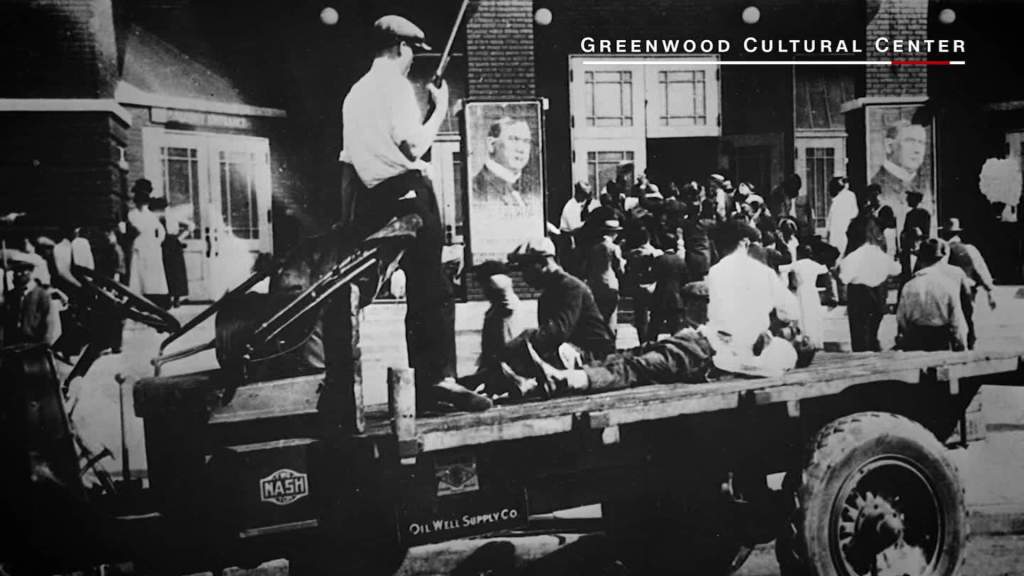

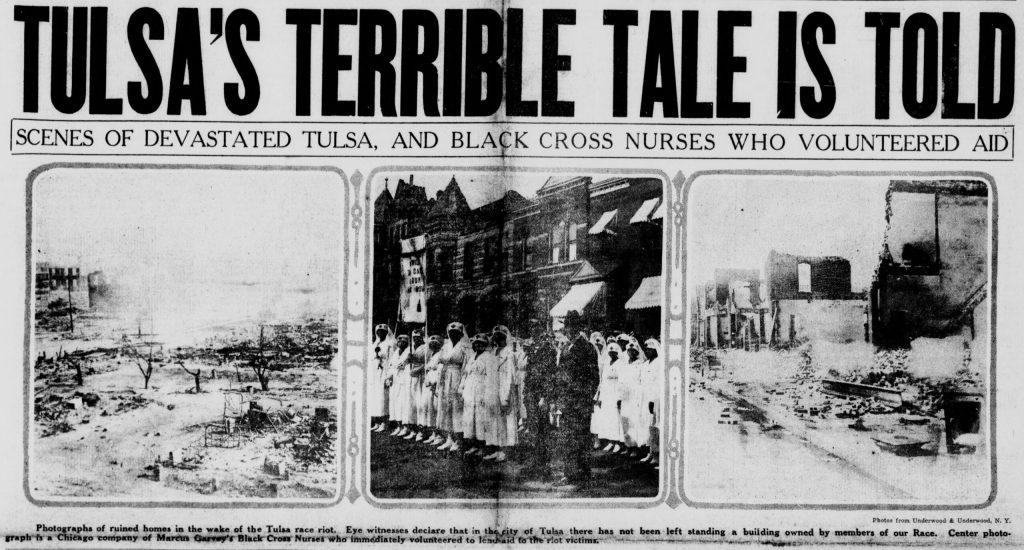

The Greenwood District descended into chaos as white mobs attacked black homes, businesses, and people, looting and destroying everything in their path. Despite the efforts of black residents, including veterans, to defend their community, they were overwhelmed by the vast number of attackers.

Instead of intervening, law enforcement frequently stood by or, in some cases, even participated in the violence. Fire trucks arrived, but instead of extinguishing the flames, they stood by and watched the community burn.

As the day went on, there were rumours that the Black community was getting ready to grow their ranks by recruiting more Black fighters from nearby areas. City officials responded by deputing hundreds of white men, giving them the power to reestablish law and order. These newly deputized individuals played an important role in the escalating violence, but what happened next shocked the entire nation for generations.

A group of white pilots, granted permission by city officials to fly, dropped firebombs on the black community, destroying homes, businesses, and churches. The bombs set buildings on fire, sending flames into the sky. Explosions and screams rang through the air as the community was subjected to extreme violence and destruction.

The devastation was catastrophic, with men, women, and children burned alive and entire neighbourhoods destroyed. Over 1,000 homes, 21 churches, 2 schools, and 600 businesses were destroyed.

Notable Black-owned businesses, including the Williams Hotel, Dreamland Theatre, and Victory Life Insurance Company, were among those destroyed, erasing the community’s economic foundation.

The Aftermath of the Tulsa Massacre

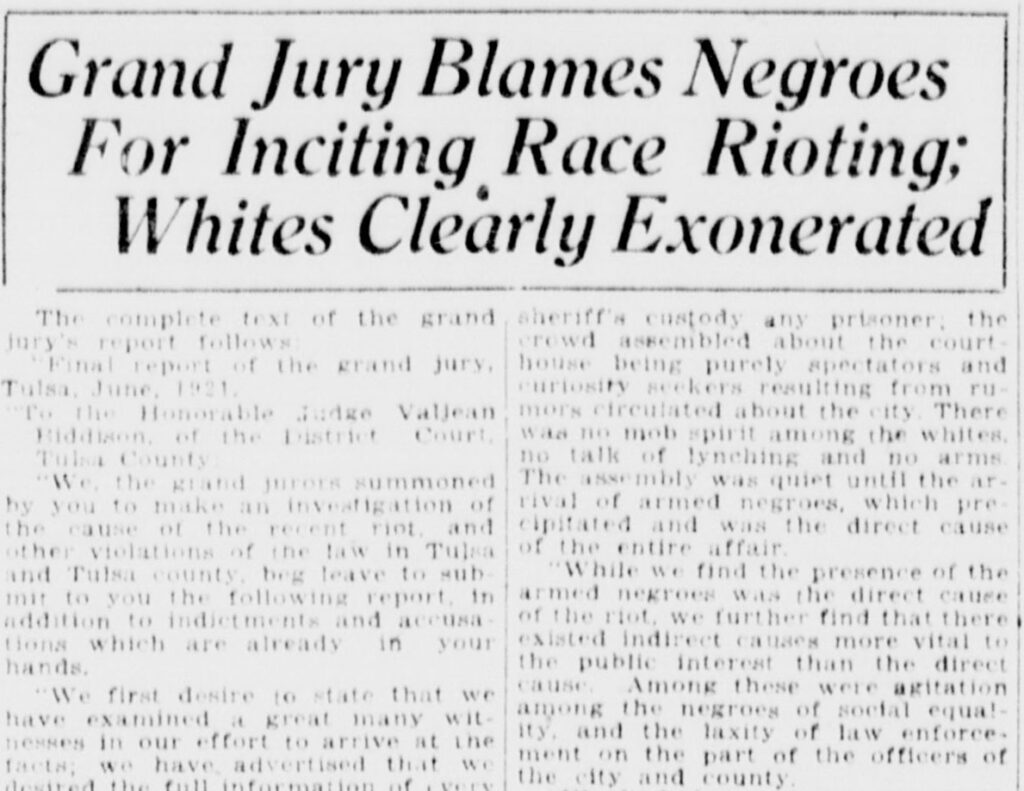

The day after the massacre, survivors were in shock, struggling to process the trauma and left facing unimaginable hardship. City officials limited relief efforts, and the government barely responded. The Tulsa County Grand Jury even blamed the victims, claiming that the violence was caused by a “Negro uprising”.

Law enforcement detained, intimidated, and disarmed Black residents, imprisoned many, and declared martial law alongside the National Guard. Many survivors had to rely on makeshift shelters for their basic needs.

Community leaders spoke out against the violence and advocated for justice, but they faced opposition. Insurance companies denied claims, citing “riot” clauses. Under President Warren G. Harding, the federal government took a hands-off approach, prioritizing racial tensions over African American rights, worsening the suffering of survivors.

The struggle for justice and accountability continued for decades, with the community’s cries for recognition and reparations largely ignored. It wasn’t until 1996, on the 75th anniversary of the massacre, that the Oklahoma state legislature officially acknowledged the atrocity and established a commission to investigate the events.

The commission’s report, released in 2001, concluded that the massacre was the result of racial tensions and that the government failed to protect the black community.

The report’s recommendations for reparations and other measures aimed to address the lasting impact of the massacre. In 2021, the city of Tulsa established a $30 million fund for reparations, a significant step towards reconciliation.

Building on this, Mayor Monroe Nichols proposed a $100-105 million reparations trust in 2025, focusing on local housing, scholarships, and economic development. Many survivors, however, saw these efforts as too late, having already spent their lives dealing with the aftermath of the massacre.

Viola Ford Fletcher, born in 1914, was only seven years old when she witnessed the destruction of her hometown, Greenwood. She spent her life advocating for justice and reparations, sharing her story in her memoir “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story” before passing away at the age of 111 in 2025.

Her brother, Hughes Van Ellis, survived the massacre and fought for justice alongside her until his death in 2023 at the age of 102. Lessie Benningfield Randle, 111, is the last known living survivor, bearing the weight of this tragic history.

Articles Sources

- Ellson, A. (2021). Don’t Let Them Bury My Story.

- Oklahoma State Legislature. (2001). Report of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission.

- Tulsa Historical Society. (2021, May 31). The Tulsa Race Massacre.

- Johnson, H. (1921, June 3). Tulsa’s Negroes Wiped Out by mob. The Chicago Defender.

- Madsen, J. (2021). The Tulsa Race Massacre: A Historical Analysis.

- Hirsch, J. E. (2002). Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race Riot and Its Legacy.

Image Sources

- Library of Congress. (2021, May). Tulsa Race Massacre: Newspaper Complicity and Coverage. Headlines and Heroes Blog. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/05/tulsa-race-massacre-newspaper-complicity-and-coverage/

- Run It Back. (n.d.). 018: A Way With Words. Substack. https://runitback.substack.com/p/018-a-way-with-words

- Arkansas Democrat Gazette. (2023, June 19). O.W. Gurley and Black Wall Street. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jun/19/ow-gurley-and-black-wall-street/

- Tulsa City-County Library. (n.d.). Tulsa and Oklahoma History. https://www.tulsalibrary.org/research/tulsa-and-oklahoma-history

- The New York Times. (2023, May 26). How Greenwood Grew: A Thriving Black Economy. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/26/headway/how-greenwood-grew-a-thriving-black-economy.html

Leave a comment