There are few events in contemporary history that are as tragic and heartbreaking as Belgium’s genocide in Congo and Germany’s genocide in Namibia. But nothing can be more disturbing than what happened to the Tasmanian aboriginal people. This is a sad story, one more in the long history of European inhumanity toward people who do not resemble them.

As we explore the history of the Aboriginals of Tasmania, we unveil the devastating repercussions of colonial expansion and the persistent invasion of indigenous lands and cultures all over the world.

This article will shed light on a painful chapter in Australian history, exposing the genocide that wiped out an entire tribe. Australia’s conscience will forever bear the scars of that tragic period of bloodshed and unspeakable suffering.

Early History of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people

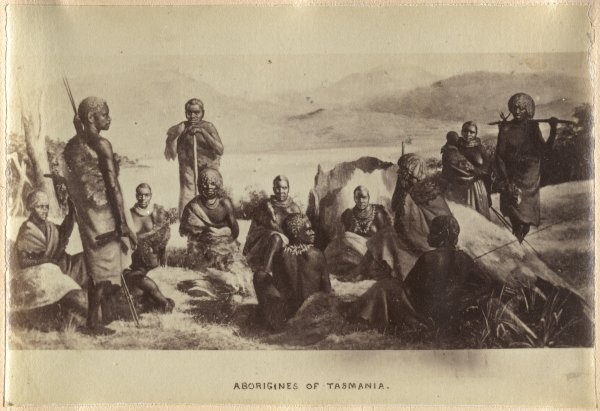

Before European invasion, Tasmania’s indigenous population, known as the Aboriginal Tasmanians, thrived in the southern region of the island. Their rich culture was made up of many ethnic groups and clans, each with its own traditions, languages, and ways of doing things.

With nine different language groups, each with its own dialects and ancestral lands, Tasmania’s Aboriginal population had a unique linguistic legacy. Careful management of these groups’ lands made sure that food resources could be used for a long time.

According to archaeological findings, Tasmanian Aboriginal ancestors travelled across a land bridge to reach the island at least 40,000 years ago. The land bridge was swept away by rising sea levels around 6000 BC, isolating the Tasmanian people and forming their distinct cultural and linguistic identity.

Read more: Exposed: The Reason White People Hate Black People is in the Bible

One of the terms the Tasmanian Aboriginal people used to refer to themselves was ‘Palawa‘, a phrase deeply rooted in their rich cultural heritage. In accordance with their customs, the “first man,” who was miraculously formed from a kangaroo by a strong creation spirit, was called “Palawa.”

The Aboriginal people believed that the kangaroo was Tarner, a powerful spirit from the time of creation and a respected ancestor of Palawa, the “first man.” This spirit figure linked the people to the lands of their ancestors and confirmed their lineage through sacred family ties.

As Europeans may try to persuade you, Aboriginal Tasmanians were not savages; rather, they were skilled hunters and gatherers who profited from the island’s natural resources. They gathered seafood, hunted land animals like possums and wallabies, and gathered edible plants from the wild. They demonstrated a balanced relationship with the land and the sea by using their ingenuity and cooperation to sustain their communities.

During the warmer months, they smartly adjusted to the island’s changing seasons by moving between the interior and the coast to get to food and resources more easily. They often went through the open forests and moorlands of the interior in groups of 15 to 50 people, like families. During the autumn and winter, they would relocate to the coast to capture seals, seafood, and other marine life. This demonstrated the extent of their understanding of the land and its cycles.

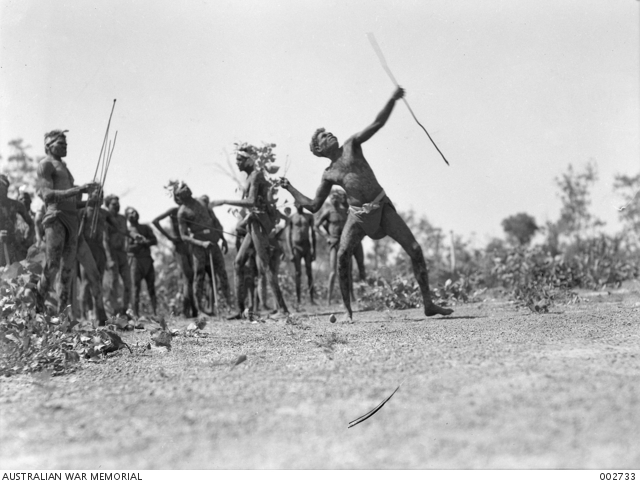

For Tasmanian Aboriginal people, hunting was a treasured custom that was frequently accompanied by lively music and followed by festive celebrations that included intricate dance, music, and engrossing storytelling. In addition to being great hunters, they were also skilled craftsmen.

They were known for making spears, waddles, and tools and weapons out of flaked stone, which showed how creative and flexible they were. Everything was fine for the Tasmanians until the British decided to unwelcomed themselves, upsetting their balance and way of life.

The British arrival in Tasmania during the 17th to 18th century had a devastating impact on the indigenous population, estimated to be between 3,000 to 10,000 individuals. Due to violence and diseases that were brought in, their numbers drastically decreased in just thirty years. Historians Geoffrey Blainey and Henry Reynolds attribute the decline to disease and genocide, with Reynolds specifically referencing the Black War.

Other historians, like Ben Kiernan, Colin Tatz, and Benjamin Madley, agree that the British massacre caused the population decline in Tasmania, which, by Raphael Lemkin’s definition in the UN Genocide Convention, qualifies as a full genocide.

Additionally, historians Ann Curthoys, Lyndall Ryan, and Naomi Parry have further defined the dangers of this period, highlighting the violent conflicts, displacement, and trauma inflicted upon the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

The Arrival of the British on Tasmanian Soil and the violence that erupted

The British arrival in Tasmania was not peaceful; rather, it resulted in the establishment of a military outpost at Risdon Cove, which invoked the flawed principle of Terra Nullius, a Latin term that represents “land belonging to no one.”

According to the white man’s mindset, this concept implied that any land they entered belonged to them. Due to their belief that they were superior to the indigenous population, European settlers appropriated the land and its resources without obtaining permission or compensation. Note that different criteria were used for different European territories, indicating that this principle was applied selectively.

By 1830, the British population in Tasmania had grown to 24,000, occupying around 30% of the island’s ancestral lands. This expansion displaced the Tasmanian Aboriginal people from their homelands, hunting grounds, and food sources, leading to widespread hunger and malnutrition. British colonizers employed violence and brutality to seize land and resources.

Many British settlers believed that forcibly removing the Aboriginal people to camps was the solution to the “Tasmanian problem,” driven by mistrust, fear, and a sense of duty. In response, the Tasmanian Aboriginal people united to reclaim their ancestral lands, sparking resistance movements that fought against injustice and asserted their rights. These movements challenged the colonial regime in various ways, protecting their traditional lands, cultures, and identities.

The British responded to Aboriginal resistance with a provocative notice, sanctioning violence against any group that challenged colonial authority, and emboldening settlers to express hostility. The authorities then deployed additional soldiers near Aboriginal settlements to suppress uprisings.

In response, the Tasmanian Aboriginals adopted guerrilla warfare tactics, launching hit-and-run attacks on British farms and settlements. These raids exploited British vulnerabilities, disrupted supply lines, and undermined their security while minimizing Aboriginal casualties.

The British viewed these attacks as a declaration of war and vowed to crush the resistance with all of their military might. The Tasmanians were prepared to lose their lives in order to defend their land. They believed that their land was worth fighting for because anything worth having is worth fighting for.

The British determined to halt the uprising and maintain their colonial control over Tasmania by employing any means necessary. This action was implemented to exhibit their authority.

In 1827, violence between Aboriginal people and British settlers intensified, with clashes resulting in fatalities on both sides. Aboriginal guerrilla attacks on farms and settlements sparked vicious British reprisals, rendering a cycle of violence.

Aboriginal warriors targeted British stock-keepers, but the British responded with disproportionate force, killing many Aboriginal people in indiscriminate raids. A notable incident involved Kikatapula, a respected Aboriginal leader, whose confrontation with a British farm overseer prompted a punitive raid by British soldiers. The raid resulted in 14 Aboriginal deaths and the capture of nine others, including Kikatapula. From then on, there was violence all over Tasmania.

Tensions escalated after the deaths of two British shepherds around Mount Augusta in April 1827. Seeking revenge, British soldiers and a pursuit party launched a dawn raid on an Aboriginal camp, resulting in the massacre of 40 Aboriginal men, women, and children.

In May 1827, an Oyster Bay group of Aboriginals killed a British stock-keeper at Great Swanport in retaliation for previous massacres. This act triggered a punitive attack by British soldiers, police, and civilians on an Aboriginal camp, further escalating the violence.

In June 1827, a large group of British settlers launched a brutal reprisal attack on the Pallittorre clan, killing between 80 and 100 Aboriginal people in a devastating massacre, reportedly in response to the killing of three British stockmen.

In September 1827, the British authorities increased their military presence in Aboriginal districts, deploying 26 field police officers and 55 soldiers to quell potential uprisings and maintain control. This aggressive strategy led to further bloodshed, and the death toll in Aboriginal settled districts rose to around 350.

In January 1828, the British leadership in Tasmania planned to remove Aboriginal people forcibly from their ancestral lands, relocating them to a remote region on the north-eastern coast with the aim of “civilizing” and subjugating them to British rule. The Aboriginal people rejected the British offer, recognizing it as a ploy to isolate and control them. They understood that the proposal would sever their ties to their land, culture, and way of life.

With diplomatic efforts stalled, the conflict escalated into further violence, with intensified clashes and attacks between the Aboriginal people and British settlers. The British authorities allowed and promoted violent confrontations to compel Tasmanian Aboriginals to relinquish their lands and relocate, employing aggressive force. They basically gave settlers the power to use force against Aboriginal people, which led to a wave of vigilantism and violence.

In the winter of 1828, some Aboriginal people, exhausted by British pressure, fled to the designated settlement. However, those who refused to surrender their land faced brutal force. In July 1828, the British 40th Regiment attacked an Aboriginal camp, killing 16 people from Oyster Cove.

The British massacre of 16 Aboriginal people from Oyster Cove sparked fierce resistance, with Aboriginal groups launching coordinated raids on British stock huts between August and October 1828, killing 15 settlers. Motivated by a desire for revenge and resistance, they implemented guerrilla tactics to disrupt British operations and challenge their authority, thereby triggering a cycle of retaliation.

After Aboriginal raids, the British government decided to start a planned campaign to wipe out the entire Tasmanian Aboriginal population. Many regard this policy as one of the most heinous instances of genocide in history. An entire race suffered greatly as a result of this decision, which was motivated by the desire to exterminate the local population and establish complete British control.

The Mass Murder of Aboriginal People in Tasmania

The British declaration of martial law in Tasmania (1828-1831) led to extreme violence, with thousands of Aboriginal people killed and 200–300 survivors forcibly relocated to Flinders Island under the guise of “conciliation” efforts led by George Augustus Robinson.

At the Wybalenna settlement on the island, they encountered appalling conditions, as disease thrived due to inadequate sanitation, and mortality rates were alarmingly high. Their mental and emotional health was severely damaged by the trauma of forced removal, cultural loss, and difficult living conditions. This initiated a new phase of trauma and adversity that would have a long-lasting effect on Tasmanian Aboriginal identity, culture, and community.

Upon the closure of the camps in 1847, the Aboriginal population on Flinders Island experienced a significant decline, reducing to less than 100 and ultimately to 40, as a result of a combination of disease, malnutrition, and despair. Only a few of the remaining survivors were able to escape the ravages.

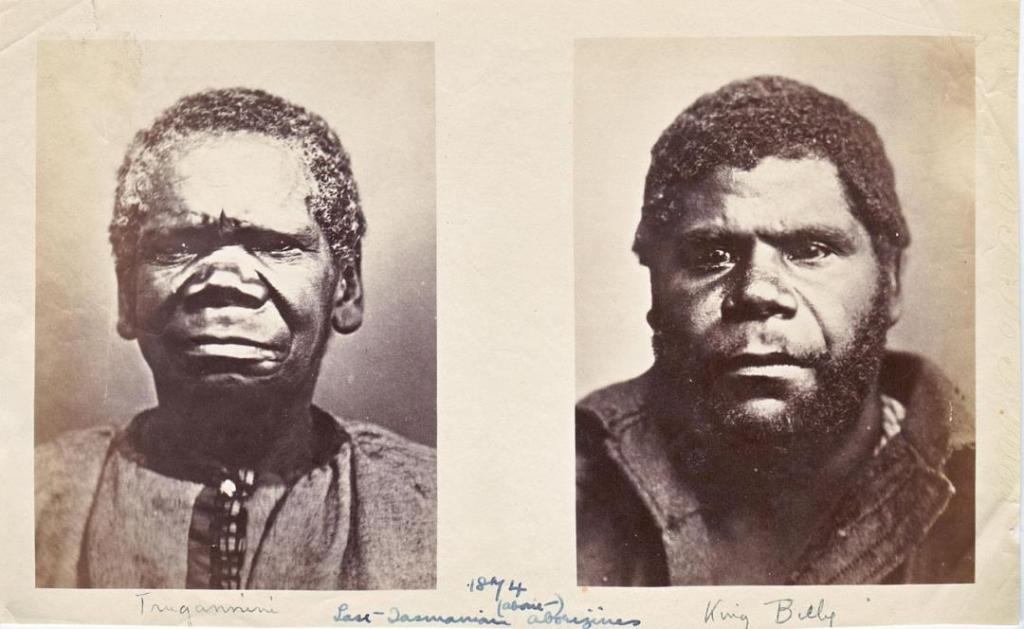

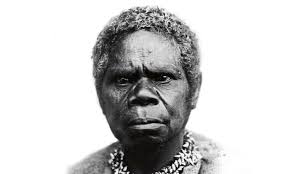

The Tasmanian Aboriginal people were wiped out as a result of a catastrophic series of events. The last full-blooded Tasmanian Aboriginal, Truganini, passed away in 1876. Her death marked the end of an era and the loss of a unique culture and way of life.

Furthermore, Fanny Cochrane Smith, who was of mixed heritage and was the last known speaker of the Tasmanian Aboriginal language, also died in 1905.

The deaths of Truganini and William Lanne marked the end of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. To make matters worse, their remains were treated disrespectfully, with Truganini’s body being displayed in public despite her wishes for cremation.

It took nearly a century to have her remains cremated and scattered as she had requested. Furthermore, preserved samples of her hair and skin were discovered, returned, and buried, bringing closure and respect to her legacy.

Conclusion

The British colonization of Tasmania was a catastrophic event that decimated the native population. Before Europeans arrived, Tasmania was home to about 10,000 Aboriginal people. After only 27 years of British rule, the population had plummeted to a shocking 2 people.

What is even more tragic is that Australia continues to celebrate Australia Day, which commemorates the arrival of the British and the genocide against Indigenous Australians.

The fact that Britain has yet to offer an adequate apology or make amends to the Australian Aboriginal people serve as a harsh reminder of how cruel the white man was to those with darker skin tones. This behaviour eventually led to institutional racism and societal biases, which many Indigenous Australians still face today.

Finally, it is disheartening to learn that there is no single international memorial for the Tasmanian genocide.

Sources

List of multiple killings of Aborigines in Tasmania: 1804-1835 | Sciences Po Violence de masse et Résistance – Réseau de recherche. (2008, March 5). https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/list-multiple-killings-aborigines-tasmania-1804-1835.html

Berk, Christopher D. (2017). “Palawa Kaniand the Value of Language in Aboriginal Tasmania”. Oceania. 87 (1): 2–20. doi:10.1002/ocea.5148. ISSN 0029-8077.

OpenLibrary.org. (1967). Daily life and origin of the Tasmanians. By James Bonwick | Open Library. Open Library. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL5531758M/Daily_life_and_origin_of_the_Tasmanian.

Lawson, Tom (2014). The Last Man: A British Genocide in Tasmania. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-780-76626-3.

Companion to Tasmanian history. (n.d.). https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/index.htm

Harman, K. (n.d.). Explainer: the evidence for the Tasmanian genocide. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/explainer-the-evidence-for-the-tasmanian-genocide-86828

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, August 1). Tasmanian Aboriginal people | History & Facts. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tasmanian-Aboriginal-people

Leave a comment