According to the latest United Nations data compiled by Worldometer, Argentina’s population stands at 46.23 million. Within this demographic, Afro-Argentines comprise a relatively small percentage, with 302,936 individuals comprising approximately 0.66% of the population.

In contrast, the majority of Argentina’s population, at least 97%, is of European descent. This demographic composition, however, is a relatively recent development and, as we are all aware, is a consequence of Spain’s decision to make Argentina white.

Around 300 years ago, there was not a single white European to be found on many shores, let alone as the dominant group in Latin America. The indigenous people who first inhabited the Americas, including Argentina, were dark-skinned. In the case of Argentina, what they don’t want you to know is that Argentina was home to dark-skinned indigenous populations.

Because there was a systematic plan to erase the presence and contributions of black people outside of Africa and the Caribbean, they came up with a plan to designate everyone black as “Afro” to hide the truth. The only purpose of this fictional “out-of-Africa” theory is to bury the fact that black people are indigenous to every continent on the face of the earth.

In historical accounts that push for a mostly European Latin America, this fact is often left out. However, authors like Aníbal Quijano, who wrote about the coloniality of power, Walter Mignolo, and Edward Telles, author of “Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America”, have revealed the truth about the dark-skinned populations of Latin America. If you want to read more about them, you can find a list of sources at the end of this article.

How did the Afro-Argentines end up as an absolute minority?

Afro-Argentines shaped Argentina’s cultural landscape, introducing rhythms like Candombe and instruments such as the bombo legüero. Their contributions to music, crafts, storytelling, cuisine, and traditional medicine have left an enduring mark on the country’s history, going beyond tango and folklore.

Argentina’s pursuit of modernization erased Indigenous and Black contributions. Leaders prioritized European culture while ignoring the value of existing communities, imposing their own image and claiming accomplishments for themselves. This narrative erased Black Argentines’ cultural legacy, associating whiteness with progress and civilization while marginalizing those with melanin-rich skin.

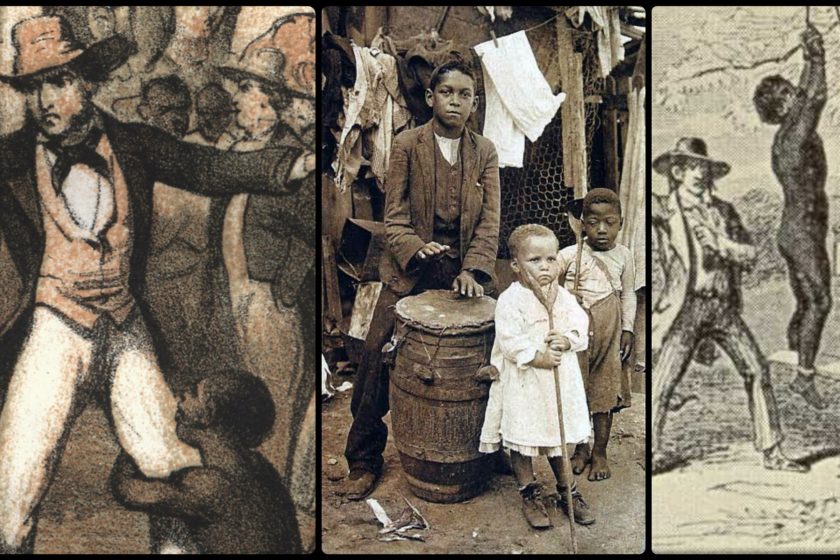

This white supremacist ideology was prevalent in European countries, influencing colonial efforts, policies, and social attitudes, with far-reaching consequences for marginalized groups. In Argentina, Spanish colonizers attempted to humiliate native populations by brutally suppressing those who resisted, mirroring the actions of Christopher Columbus and other colonizers.

The Spanish introduced the transatlantic slave trade to Argentina, establishing a slave system that had far-reaching consequences for the country’s history and population. During the Middle Passage alone, approximately 1.8 million enslaved black people died. In 1853, Argentina abolished slavery, freeing newborns born to enslaved mothers and granting freedom to those entering the country. However, this resulted in a new era of marginalization for Afro-Argentines because implementation was delayed in Buenos Aires until 1861, and their struggles persisted.

As Argentine leaders pursued European-inspired modernization, they marginalized Afro-Argentines, seeing them as a hindrance to progress. Strict laws denied them social services, healthcare, and benefits, resulting in dire consequences such as high infant mortality, poverty, and inequality.

The white Argentine government also targeted Afro-Argentine males, enlisting them into the Paraguayan War with little training and resulting in devastating losses. Despite their sacrifices, their contributions were disregarded, thereby leading to their marginalization.

The Argentine government went on to use more biological tactics, such as exploiting cholera and yellow fever outbreaks, which disproportionately devastated Afro-Argentine communities, further reducing their numbers.

This was a watershed moment in their history, bringing unprecedented challenges to survival and identity. Similar patterns of racial violence and marginalization emerged throughout Latin America, as countries like Brazil and Cuba implemented policies aimed at Black people.

The Argentine government took their hatred a step further by introducing Blanqueamiento, a plan to attract European immigrants and increase the white population by offering incentives such as citizenship and social benefits. This initiative, influenced by Juan Bautista Alberdi’s ideas, sought to shift demographics, further marginalizing Afro-Argentines who were already suffering from genocide and violence.

Between 1870 and 1930, over seven million immigrants arrived, mainly from Spain and Italy, though about half eventually returned home. This influx of European settlers reshaped Argentina’s demographics, solidifying its identity as a predominantly white nation.

Click here to find the 25th amendment.

By the early 1900s, Argentina’s efforts to exterminate Afro-Argentines appeared to be successful. A 1905 Caras y Caretas article claimed that the Black population had “disappeared,” praising the “white flowers” of the “African tree.” This was the pinnacle of racial cleansing, cementing Argentina’s identity as a predominantly white country, with Afro-Argentines reduced to a shadow of their former selves.

The Faces behind the whitening (Blanqueamiento) of Argentina’s Population

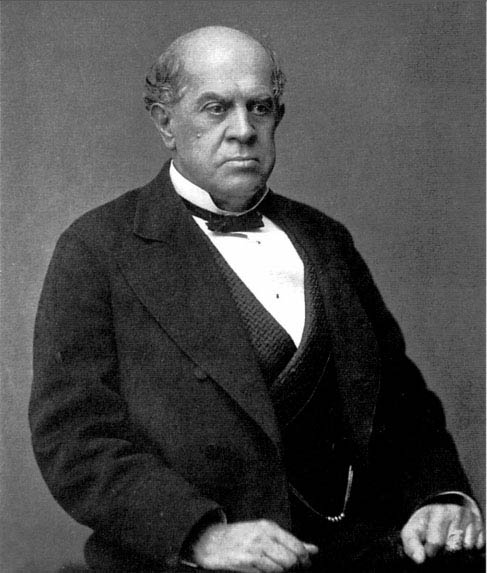

One of the biggest faces of Argentina’s Whitening (Blanqueamiento) was none other than the dreaded, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who was a European Argentine activist and the 7th President of Argentina from 1868 to 1874.

Sarmiento’s presidency promoted European-style modernization, increasing white presence in Argentina. His racist views, as evidenced by his writings and policies, advocated for a white, European-dominated Argentina that erased indigenous roots. His comparison of mixed-race Gauchos to fertilizers revealed his contempt for non-white people. Policies like forced conscription, executions, and segregation bolstered Argentina’s apartheid regime, persecuting Afro-Argentines to achieve an all-white vision.

Sarmiento outlined his demographic vision for Argentina in his 1848 statement in El Progreso. His presidency implemented policies that impacted Afro-Argentines, most notably their exclusion from the 1875 national census.

In addition, his government implemented segregation and failed to provide adequate medical facilities, which caused healthcare problems. This was particularly evident during the cholera outbreak, when Afro-Argentines encountered challenges in obtaining treatment. Black men in Argentina were subjected to harsher penalties than their European counterparts, resulting in intimidation and fear aimed at controlling Black families and communities, similar to Jim Crow-era racism in the US.

Afro-Argentine women were also significantly impacted, and some sought legal assistance but were unsuccessful. With few options, some went as far as forming relationships with white-European men in order to survive, pressuring them to “pass” mixed-race children as white or Amerindian. Economic hardship forced many Afro-Argentines and mulattos to adopt new identities such as criollo, morocho, and pardo, further erasing their Black roots.

While in exile in Chile as a result of the politics being played at that time with the then military dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas, Domingo Sarmiento made a damning statement against blacks in Argentina, and I quote him:

“We must be reasonable with the Spaniards,” he wrote, “by exterminating a savage people whose territory they were going to occupy, they merely achieved what all civilized people have done with savages, what colonization did consciously or unconsciously: absorb, destroy and exterminate.”

Sarmiento wrote “Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism” (1845)

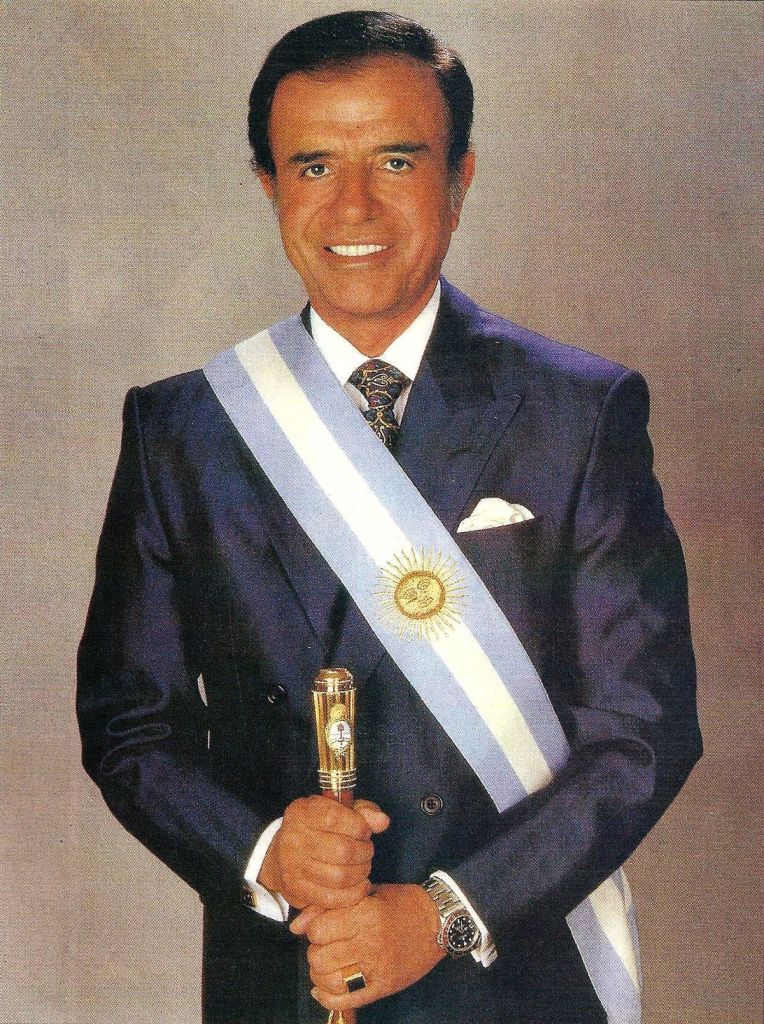

This erasure was so widespread that even former President Carlos Saúl Menem later said wrongly that there are no Black people in Argentina, calling the problem a Brazilian one.

The historical narrative of Afro-Argentines was gradually erased, including figures such as Bernardino Rivadavia, the country’s first president of dark skin who was later depicted with European features. Even the Argentine national football team, La Albiceleste is a clear reflection of the country’s troubled history with racism. The team’s European-dominated line up is a result of Argentina’s “White Mestizaje” ideology, which emphasized European superiority while attempting to erase indigenous identities.

Furthermore, the recent incident in which members of Argentina’s football team made hurtful remarks about the African heritage of a French national team player highlights the deep-seated racism that continues in Argentina.

Even in the face of historical erasure and systemic racism, Afro-Argentines still succeed in maintaining their cultural identity. Neighbourhoods such as San Telmo and La Boca in Buenos Aires demonstrate the strength and longevity of Afro-Argentine communities.

Conclusion

The Internet has revealed the atrocities committed against Afro-Argentinians by European colonists, the majority of whom came from Spain or Italy. Many European slave traders and colonists believed that the only way to modernize their nation was to get rid of anything black-related.

Read more: 10 countries with the highest black population outside of Africa

This inhumane act was committed not only in Argentina, but in virtually every nation worldwide, particularly in the continents of South and North America, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, India, and Canada.

Because most historical data and events have been erased, most of us are unaware of the existence of black people outside of Africa and the Caribbean, even in predominantly white areas.

Credit

In addition to myself, other scholars have attempted to investigate the mystery surrounding the disappearance of the black population in Argentina. One renowned, notable scholar I can thank is Erika Edwards.

At the time of completing her research on the afro-argentine, she held the position of Associate Professor of Colonial Latin American History at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. Her research is centered around Argentina, the African Diaspora, urban history, sexuality, motherhood, and education. She is the author of the following publications concerning the black population of Argentina:

- The Making of a White Nation: The Disappearance of the Black Population in Argentina,” History Compass (online) June 2018 The Making of a White Nation

- A Tale of Two Cities: Buenos Aires, Cordoba, and the Disappearance of the Black Population in Argentina” The Metropole, the official blog of the Urban History Association, May 2018 A Tale of Two Cities

- Pardo is the New Black: The Urban Origins of Argentina’s Myth of Black Disappearance” Global Urban History Blog, Dec 2016. Pardo is the New Black

You can find out more by visiting her website.

Other Sources

Telles, E. E. (2014). Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, race, and color in Latin America. University of North Carolina Press.

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533-580.

Mignolo, W. D. (2005). The idea of Latin America. Blackwell Publishing.

Leave a comment